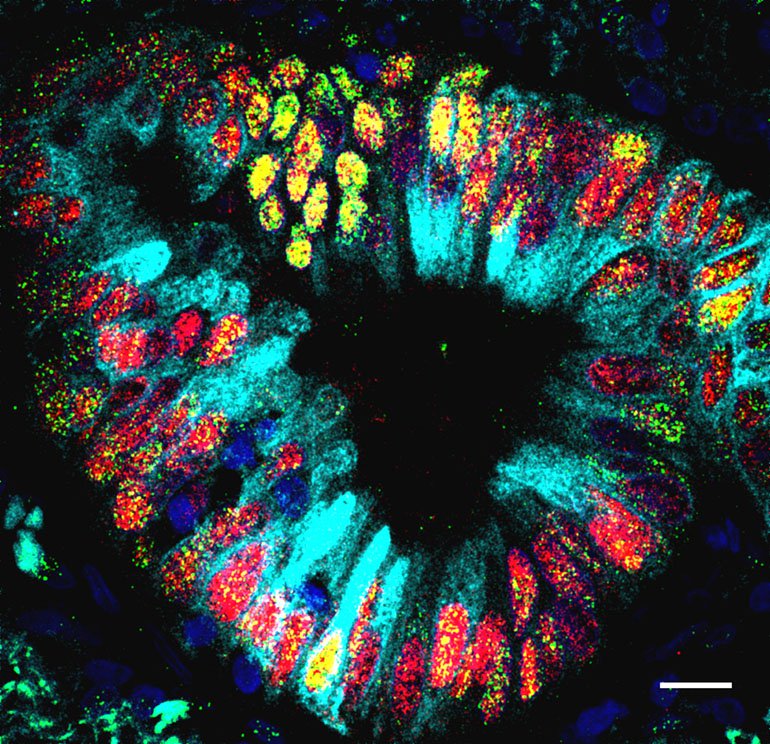

Recently, researchers from Duke University were surprised to spot a miniature digestive system — a stomach, duodenum, and small intestine — hidden among the cells of lung tumor samples.

This finding was published in Developmental Cell, a scientific journal of cell and developmental biology. Researchers discovered that these cancerous cells had lost a gene called NKX2-1. This gene acts as a master switch, which tells lung cells how to develop.

It seems that in the absence of this gene, cells follow the path of their nearest developmental neighbor and begin to develop like the gut. This incredible ability to change shows the amazing resilience and plasticity of cancer cells, which gives them an extremely powerful way to fight off treatments.

“Cancer cells will do whatever it takes to survive,” lead author Purushothama Rao Tata said in a statement. “Upon treatment with chemotherapy, lung cells shut down some of the key cell regulators and pick up the characteristics of other cells in order to gain resistance.”

Tata and his team worked on mouse models by removing the NKX2-1 gene from the lung tissue. They found that tissues that normally appear only in the gut began growing in the lungs of the mice.

“Cancer biologists have long suspected that cancer cells could shapeshift in order to evade chemotherapy and acquire resistance, but they didn’t know the mechanisms behind such plasticity,” says Tata.

“Now that we know what we are dealing with in these tumors – we can think ahead to the possible paths these cells might take and design therapies to block them.”