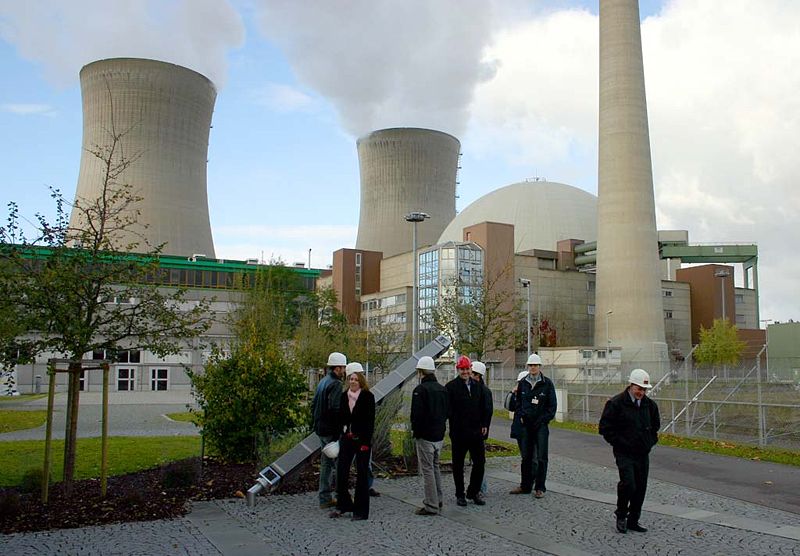

Power plants use a lot of water for cooling. But do you have any idea of how thirsty these power plants really are?

Approximately 39 percent of all freshwater in the U.S. is used for the cooling needs of electric power plants, which boil water to create steam that, in turn, drives turbines to produce electricity.

With water conservation becoming a major environmental issue for power plants, Massachusetts Institute of Technology researchers offer a new technological solution that could help recover water that is currently being lost.

A new system could provide a low-cost source of drinking water while cutting the operating costs of power plants and revolutionizing seawater desalination

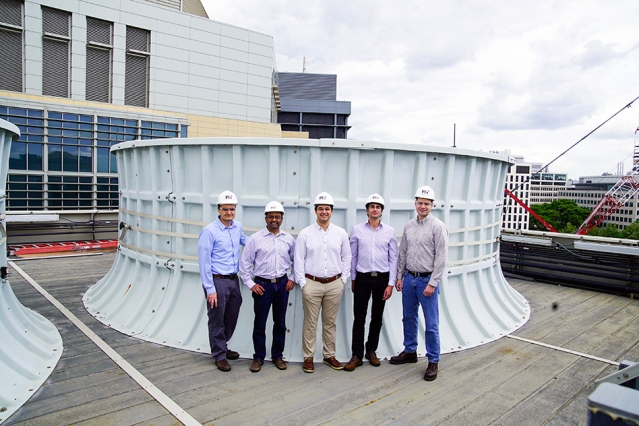

The researchers improved the efficiency of fog collectors by tapping electrical forces to recover water that was being lost in the plumes rising from the cooling towers of power plants.

From the MIT website: “When air that’s rich in fog is zapped with a beam of electrically charged particles, known as ions, water droplets become electrically charged and thus can be drawn toward a mesh of wires, similar to a window screen, placed in their path. The droplets then collect on that mesh, drain down into a collecting pan, and can be reused in the power plant or sent to a city’s water supply system.”

This amazing technique could help in providing clean, safe drinking water in coastal cities where seawater is used to cool local power plants.

Kripa Varanasi, associate professor of mechanical engineering at MIT, said, “It’s distilled water, which is of higher quality, that’s now just wasted. That’s what we’re trying to capture.

“A typical 600-megawatt power plant could capture 150 million gallons of water a year, representing a value of millions of dollars. This represents about 20 to 30 percent of the water lost from cooling towers. With further refinements, the system may be able to capture even more of the output.”

Researchers explained that installing this system would cost about one-third that of building a new desalination plant and its operating costs would be about one-fiftieth. Moreover, this installation is without any environmental footprint and it would pay back the cost of its installation in about two years.

Varanasi said, “This can be a great solution to address the global water crisis. It could offset the need for about 70 percent of new desalination plant installations in the next decade.”