Scientists from Worcester Polytechnic Institute (WPI) have found a technique to use spinach to build a working human heart muscle. This technique will be of great help in solving problems related to repairing damaged human organs.

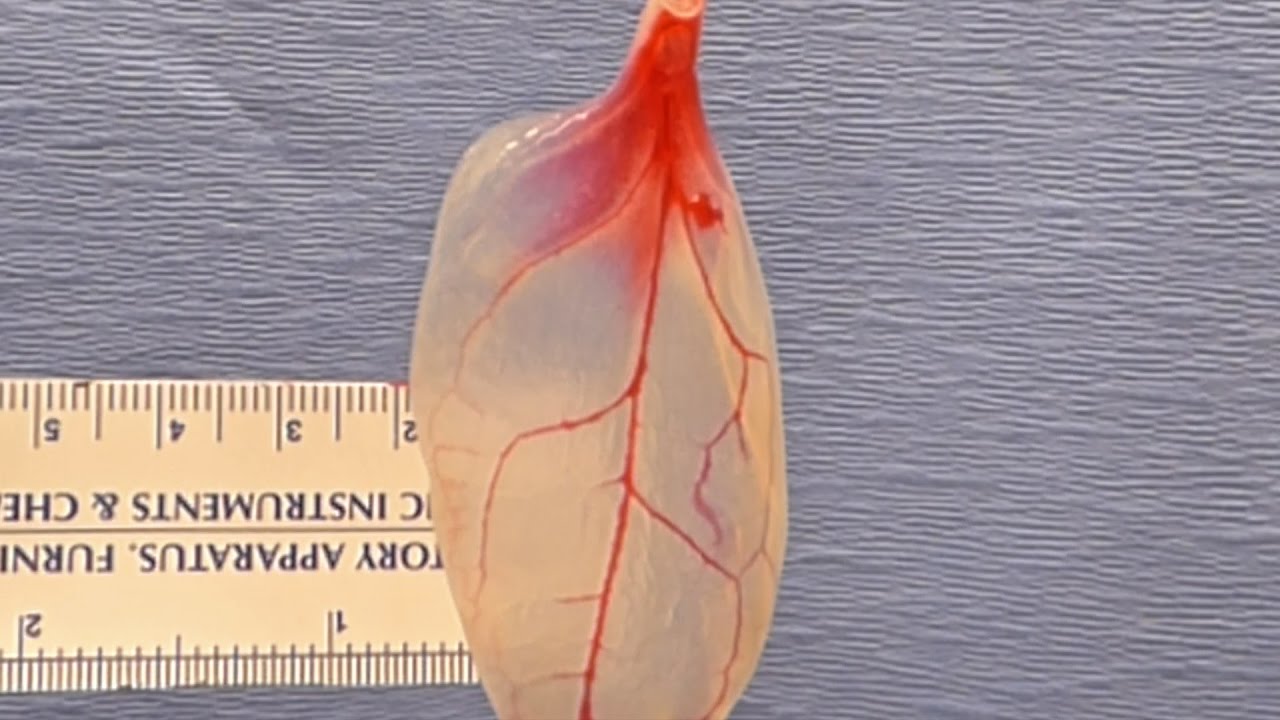

No doubt, spinach alone can’t pump anyone up. However, spinach has a network of veins through its leaves just as we have blood vessels running through our heart. Moreover, spinach was found to be the closest to a heart tissue since it has a high concentration of vessels.

Such physical properties in spinach made it useful in building functioning human heart tissue, complete with veins that can transport blood.

Blood vessels in the human body help in transporting oxygen and other nutrients. So if biomedical engineers have to build a lab-grown tissue sample, they need to build a working network of blood vessels which are very fine (capillaries, which are only 5 to 10 micrometers wide).

To solve this issue, researchers turned a spinach leaf into living heart tissue by using the tiny network of veins which are already present in this plant.

Scientists wrote in their paper published in the journal Biomaterials, “Plants and animals exploit fundamentally different approaches to transporting fluids, chemicals, and macromolecules, yet there are surprising similarities in their vascular network structures.”

Researchers used the process of decellularization to flush the plant cell material out of a spinach leaf.

Lead researcher Joshua Gershlak, said, “I had done decellularization work on human hearts before, and when I looked at the spinach leaf, its stem reminded me of an aorta. So I thought, let’s perfuse right through the stem. We weren’t sure it would work, but it turned out to be pretty easy and replicable. It’s working in many other plants.”

The research paper explains, “Currently, it is as yet unclear how the plant vasculature would be integrated into the native human vasculature and whether there would be an immune response. We really believe that this scaffold has the capability to help treat patients. We have a lot more work to do, but so far this is very promising.”