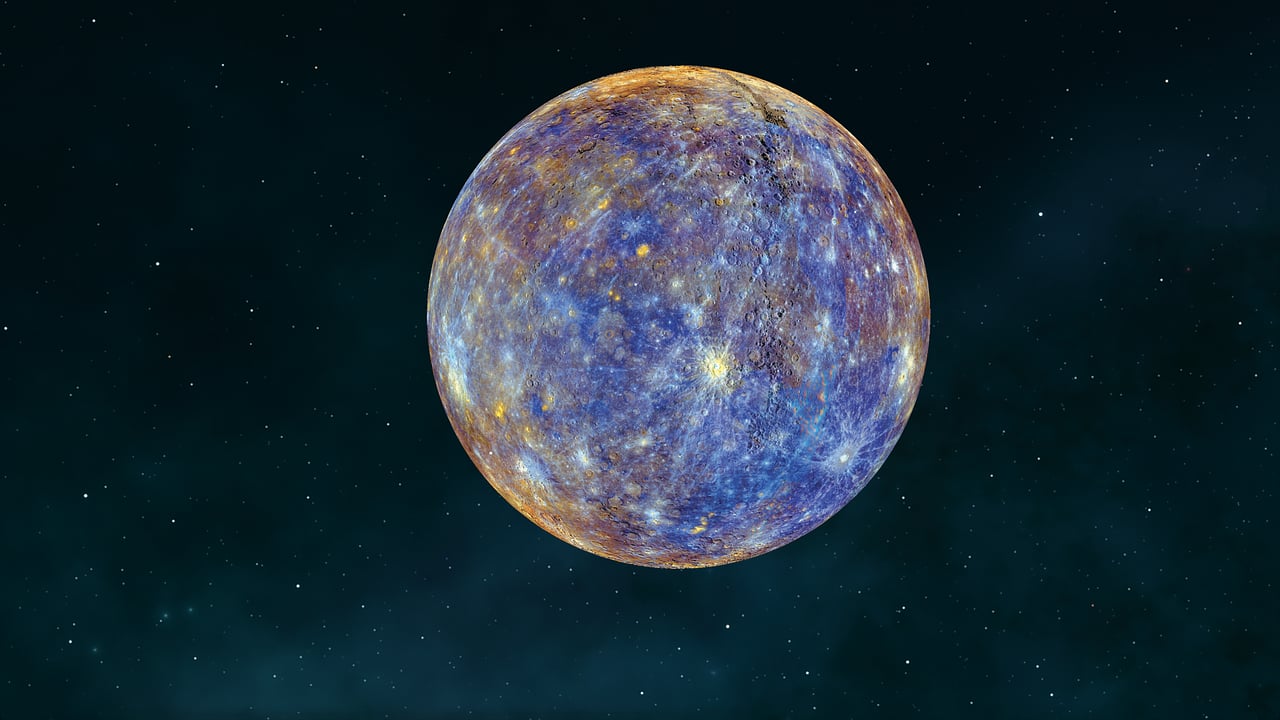

Mercury, the smallest and closest planet to the Sun, is undergoing a reduction in size. As it cools, its interior contracts, leading to surface buckling and the formation of wrinkles known as lobate scarps. These scarps can stretch for hundreds of kilometers and rise tens of kilometers in height. They are believed to originate from the compression and folding of the planet’s crust.

Uncovering Evidence of Ongoing Shrinkage

While scientists have long recognized Mercury’s gradual shrinkage, the exact extent of this phenomenon has remained uncertain. Previous models and observations had suggested a potential decrease in Mercury’s radius of up to 7 kilometers.

However, a recently published study in Nature Geoscience, led by Benjamin Man, a research student at the UK’s Open University (OU), has presented compelling evidence that Mercury is currently and actively undergoing shrinkage. Man conducted a comprehensive global survey of Mercury using data collected during NASA’s Messenger mission, conducted from 2011 to 2015.

Researchers utilized scarps as evidence of Mercury’s ongoing reduction in size. They turned their attention to grabens, shallow landforms formed by the movements of scarps, to confirm their continued activity. By measuring graben depths using shadow lengths and spacecraft positions, they estimated that many of these features formed within the past hundred million years. This underscores Mercury’s dynamic geological processes.

Mercury’s Shrinkage: A Window into Its History

Mercury’s shrinking process resembles the way an apple shrinks as it dries out. However, Mercury is shrinking due to cooling, not water loss. This intriguing phenomenon provides valuable insights into the planet’s formation and history.

Regarding Mercury’s future, it remains uncertain how long the shrinking will persist or to what extent the planet will further reduce in size. Nonetheless, it is likely that Mercury will eventually reach a point where its interior no longer cools, and its surface stops contracting, signifying its final size. It is also conceivable that Mercury might collide with the Sun, although this is not expected to occur for billions of years.

In the interim, scientists will continue their studies of Mercury to deepen their understanding of its shrinking process and its implications for the planet’s future.