Imagine leaving your house in the morning and not knowing what the day’s weather will be or making weekend plans without a clue as to whether or not a storm is brewing. A century ago, that was the reality. For the average person, any weather predictions were made based on observations and knowledge of typical patterns (it’s July, so it’s going to be warm) and little more than that.

It wasn’t until the 1940s that meteorologists had radar as a tool for predicting the weather, having relied largely on observations from weather balloons for the previous two decades. In the 1960s, the first weather satellites were launched, returning images of clouds from outer space several times a day — and by the turn of the 20th century, those satellites were returning even more data, and more often.

Today, weather forecasts are based on a never-ending stream of data collected via radar and satellite, and processed by high-powered computers throughout the entire day, giving everyone with a mobile device or a computer access to up-to-the-minute reports about the current conditions and what’s coming. We know, down to the very minute, when those menacing thunder clouds are going to ruin our picnic — and whether or not we should plan for a snow day later in the week.

Still, even with all of these advances, there is still some unpredictability in predicting the weather, especially when it comes to severe weather. While meteorologists are able to use current technology to gauge the likelihood of severe weather events like tornadoes, there are still limitations to the technology that prevent them from issuing advance warnings. In the case of tornadoes, for example, warnings are typically issued only a few minutes before the twisters form, giving people limited time to get to safety. In the case of other weather events, such as hurricanes, forecasters are already able to predict the formation and track of a storm several days in advance, but there is still a great deal of guesswork that goes into gauging the actual track and severity of the storm.

For this reason, researchers and engineers at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) are working on improving radars, satellites, and supercomputers to improve data collection abilities and analytical accuracy, effectively increasing the warning times for severe weather events.

Improving Radars, Satellites, and Computers

Most weather is predicted using radar. However, when it comes to tornadoes, every second counts, and current radar technology is not advanced enough to catch nascent tornadoes as they form.

All radar works the same way: The radar sends out radio waves that reflect off particles in the atmosphere, such as raindrops or ice, and then measures the strength of the returning waves and the length of the round trip for the waves, which indicates the location and intensity of the precipitation. The National Weather Service takes it one step further by using Doppler radar, which also measures the frequency change in returning waves to indicate the direction and speed at which the precipitation is moving. With this information, forecasters can spot rotation occurring inside thunderstorms before tornadoes form, and issue the appropriate warnings.

However, because it can take as long as six minutes for a Doppler to complete a scan of the environment, it limits the amount of time that forecasters have to warn people in the path of the storm. By upgrading the radar to phased-array radar, which sends out multiple beams simultaneously, it can potentially reduce the time needed to scan a storm to less than a minute, detecting changes that lead to tornadoes more quickly. These radars also use NCO to assist in collecting information that isn’t currently easy to collect, such as changes in wind fields that often precede changes in storm intensity, allowing for better predictions of all types of severe weather.

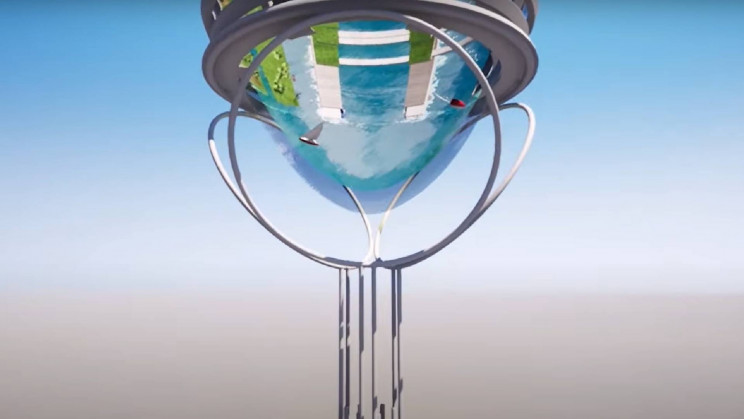

It’s not only radar that will be undergoing upgrades, though. NOAA is also launching new low Earth orbit (LEO) satellites that contain updated hardware and more sophisticated instruments. These satellites will collect data for computer models that will improve weather forecasts, including hurricane tracks and intensities, severe thunderstorms, and floods. Using this data, the National Weather Service and NOAA will be able to improve their forecast models to better match others, such as the European models, which are generally viewed as more accurate.

So while weather forecasting has come a long way from the days of looking out the window and bringing an umbrella “just in case,” it’s still evolving. Additional changes in how we produce and use power, and analyze weather data, will undoubtedly change weather forecasting even more. Until then, we can expect better, more accurate warnings for severe weather, and fewer tragedies as a result.