Infection with the influenza virus leads to lung injury through inflammation over-activation, causing collateral damage to cells required for breathing that can threaten life. However, a scientific team successfully found a new drug that can prevent flu-related lung injury.

After doing a series of experiment mouse models, scientists from St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, University of Houston, Tufts University School of Medicine, and Fox Chase Cancer Center have created a new drug, called UH15-38, which not only prevents runaway inflammation but also allows the immune system to handle the virus, even when late infection.

Findings show that the drug protected mouse models from similar amounts of influenza that humans experience at low doses. With a high drug dose, animals could be protected from an infection with a substantial amount of virus, which would usually lead to death.

In addition, it is also recorded as a notable achievement for an influenza therapeutic because the models were protected even if they received the dose 5 days later after the first infection while modern antiviral drugs need to be used within the first few days of infection to be effective.

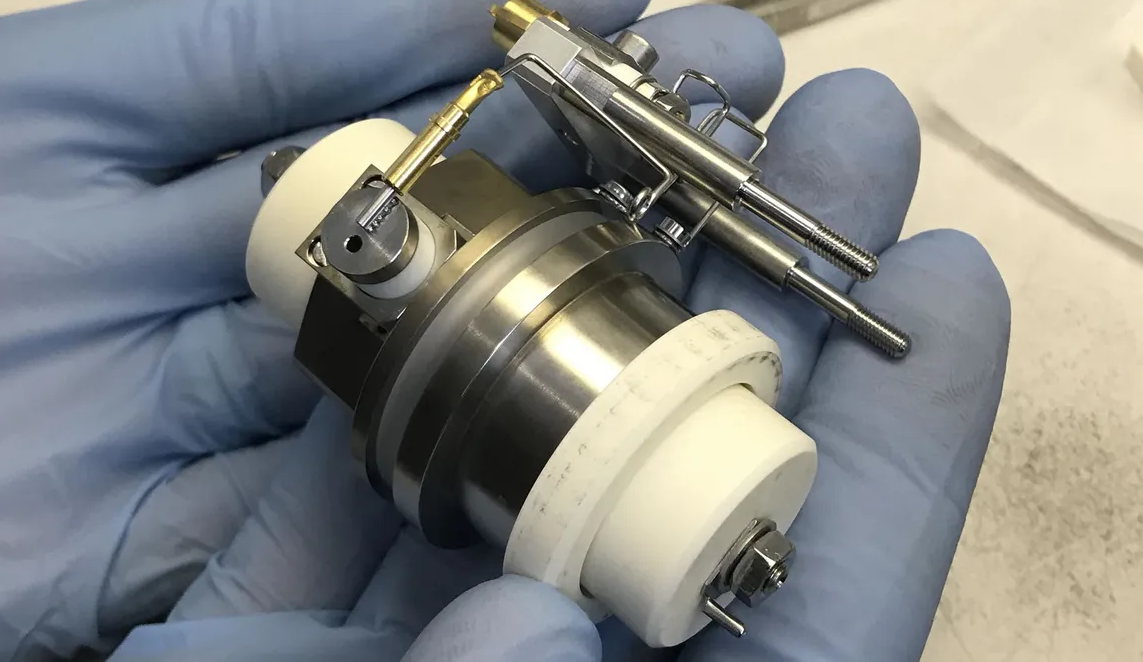

The new drug inhibited one part of a major inflammation protein in immune cells, known as Receptor-Interacting Protein Kinase 3 (RIPK3), which controls two cell death pathways in response to infection: apoptosis and necroptosis. In that, necroptosis is highly inflammatory and apoptosis is not.

Designed to prevent RIPK3 from starting necroptosis while maintaining its pro-apoptotic properties, UH15-38 helps the animals do better when just necroptosis is knocked out while still having apoptosis, meaning still gets rid of infected cells but it isn’t as inflammatory.

Not only that, the team also found a specific set of cells in the lung that are collateral damage in the runaway inflammatory response through many prior studies. These cells, Type 1 alveolar epithelial cells, respond to let oxygen in and carbon dioxide out. As so, the loss of these cells leads to a lack of ability to breathe.

The study also proved that this group of breath-taking cells was spared in the presence of UH15-38. The drug makes it a promising candidate to move forward toward the clinic as it can dampen influenza-caused inflammation while leaving viral clearance and the other functions of the immune and tissue responses intact.