You can’t see it or smell it, but the effects of ocean acidification are very visible and are very real. Our planet’s ocean waters are about 30% more acidic than they were at the dawn of the Industrial Revolution. Coral reefs, which occupy a fraction of a percent of the oceans, yet “host” 25% of the world’s ocean species, are rapidly dying. Coral is made from calcium carbonate, which dissolves in an acidic solution.

Anyone who has ever explored a healthy, thriving coral reef knows it is tantamount to an out-of-body experience. Your sight is thrilled with the eye candy of colors and shapes, your heart is touched by the sheer diversity of creatures that fill specific niches and serve certain roles, and your spirit is calmed and cradled in the buoyant, salty water. It is a humble privilege to be an observer to the coral reef’s syncopated dance of life.

But, if you have ever witnessed a dead, bleached out coral colony in comparison, and realize what has been lost, it is a mournful devastation of what was once spectacular. And it is almost always a result of shameful human behavior and indifference.

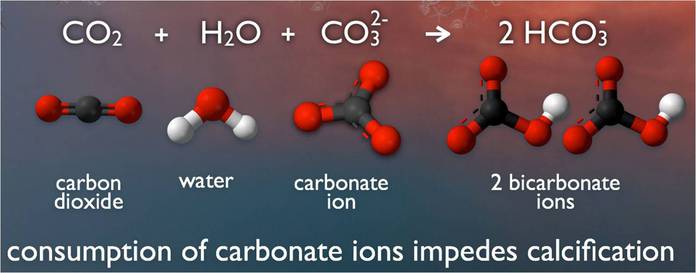

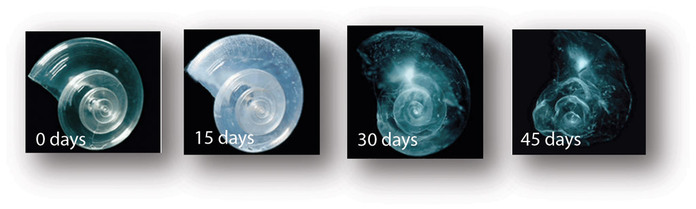

Aside from their visual splendor, the world’s coral reef systems provide food and income for more than a billion people. They are primal to the ocean food chain and crucial to human existence. Coral, a living colony of polyps, are made of calcium carbonate. So are shells, such as clams and oysters. But, acid dissolves calcium carbonate, making it difficult for shells, essentially skeletons, to form.

Acidity is measured on the pH scale, which has a range of 0-14. Neutral is in the middle and the lower the number, the more acidic a substance. Acidification refers to a shifting to a lower pH over time. According to NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration), “Since the beginning of the Industrial Revolution, the pH of ocean surface waters has fallen by 0.1 pH units. Since the pH scale, like the Richter scale, is logarithmic, this change represents approximately a 30 percent increase in acidity.”

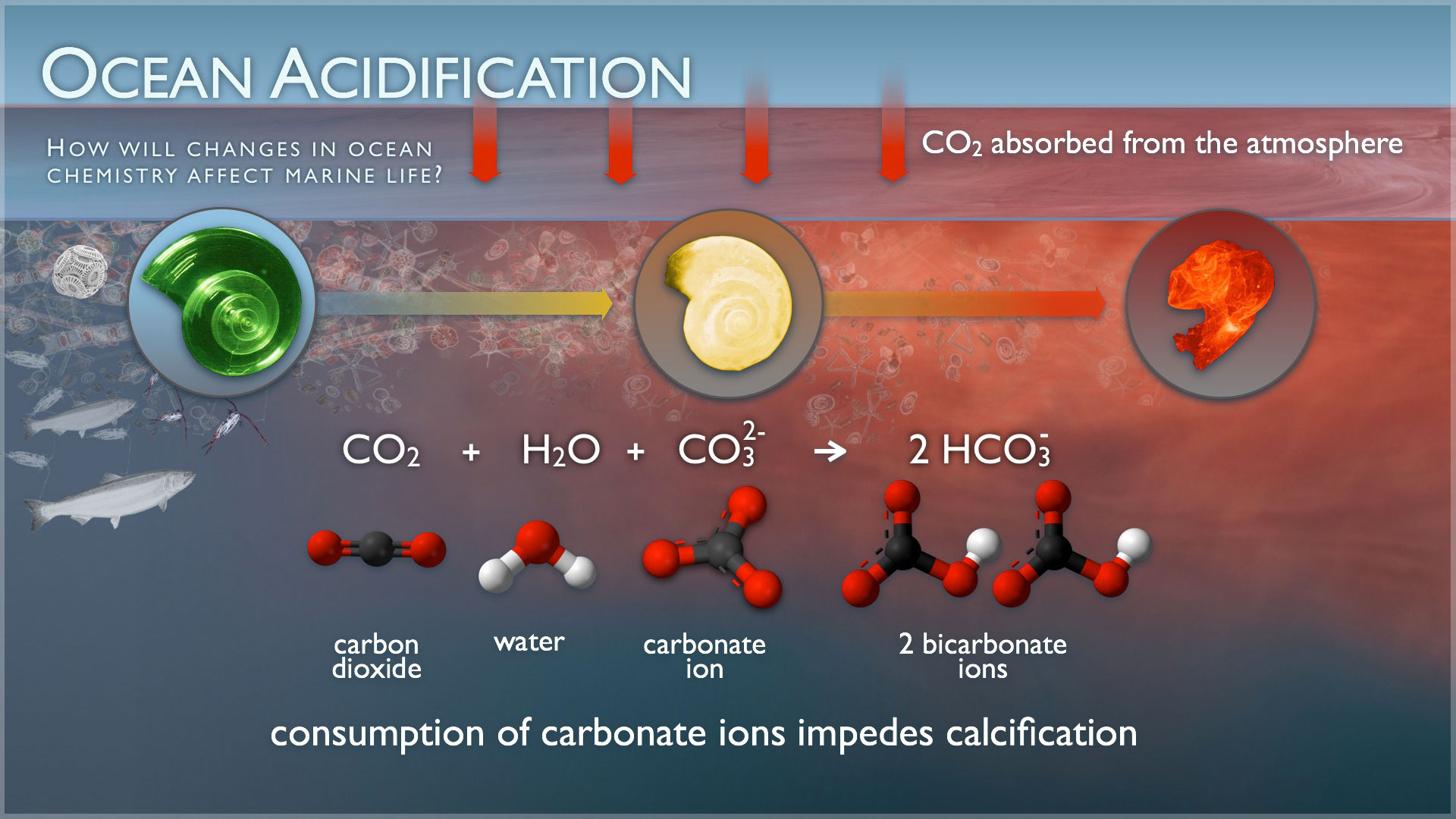

Saltwater is awash in calcium carbonate minerals, the building blocks of skeletons. But, carbon dioxide (CO2) causes a chemical reaction when absorbed by seawater, lowering the pH and affecting the saturation levels of calcium carbonate available for shells to form and maintain structural integrity. This poses an obvious threat to calcifying species such as clams and oysters, as well as corals and even calcareous plankton, causing a pejorative effect throughout the entire food chain.

It is not clearly known what effects ocean acidification will have on all species, as some are certainly more susceptible to acidic concentrations than others. But, there is clear evidence that, aside from dissolution of calcium carbonate, the higher concentrations of CO2 affect the rate of growth of sea flora. Just as CO2 is necessary for plant growth on land, so it is with ocean plants. As carbon dioxide is absorbed, an overabundance of sea grasses and algal blooms may out-compete with other species.

One outlier of particular interest to scientists is the Pacific Ocean archipelago of Palau, which is an area of naturally occurring low pH where the corals are not adversely affected by the high acidity. The Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute (WHOI) is currently studying various coral reefs where low pH occurs naturally so as to better understand their adaptive process.

But, adaptive processes take evolutionary time. And, the effects of ocean acidification are certainly a bi-product of human industry. With so much at risk, and such uncertainty of outcome, this might be a case where we should operate under the “Precautionary Principle” rather than take the gamble that may result in dire consequences.

NOAA tells us, “Ocean acidification is an emerging global problem. Over the last decade, there has been much focus in the ocean science community on studying the potential impacts of ocean acidification. Since sustained efforts to monitor ocean acidification worldwide are only beginning, it is currently impossible to predict exactly how ocean acidification impacts will cascade throughout the marine food chain and affect the overall structure of marine ecosystems. With the pace of ocean acidification accelerating, scientists, resource managers, and policymakers recognize the urgent need to strengthen the science as a basis for sound decision making and action.”

Let’s hope so!