Who could imagine that a creature whose fur houses roundworms and cockroaches, as well as numerous types of fungi, could actually hold a key to curing some of our most pesky infections? So much for the sterile environment theory. But don’t cozy up to any furry sloth friends just yet.

For most people, the very idea of bacteria on our skin and in our bodies carries a cringe factor. But researchers are beginning to appreciate the symbiotic relationships between beneficial bacteria and their hosts. There is an important balance that must be maintained for the benefit of both.

Unfortunately, we humans are only now coming to appreciate how our excessive use of antibiotics and antibacterial soaps, in our escalating war on bacteria, has led to the ugly blowback of antibiotic-resistant “superbug” strains. Such folly has left us with a humble realization that we would net better results from working with nature’s beneficial properties of enhancement and holistic, whole body, healing.

To be sure, the advent of penicillin and other antibiotics saved humanity from a host of horrific endings and was our first understanding of how the microbiome holds tools for our very survival. It’s a darn good thing evolution provided us with our human brain to think our way out of dire situations because this furless, featherless, fragile sack of a body is prone to temperature gradations, punctures, and all sorts of bacterial and viral diseases.

This new attitude of seeking to ameliorate the beneficial rather than eradicate the detrimental has scientists looking in remote places for unique organisms. One such place is the Panamanian rainforest.

The three-toed sloth (Bradypus variegatus), with its slow motility and long, course strands of fur, provides a perfect opportunity to examine the multitude of both macro and micro-organisms living on it in a symbiotic relationship. The algae that give sloth fur its green tint provide camouflage against the green jungle and gain a constant source of moisture from the unique sloth fur. But they are only the most obvious of the fungi and other organisms residing there.

The most exciting revelation is that some of the bioactive compounds appear to be effective against the malaria parasite, the tropical Chagas disease, and even against the MCF-7 form of breast cancer. There are also numerous other antimicrobial properties that may prove useful in developing new and more effective antibiotics (or even probiotics or “symbiotics”). Researchers even found one species of fungus that was effective against the most difficult strains of MRSA.

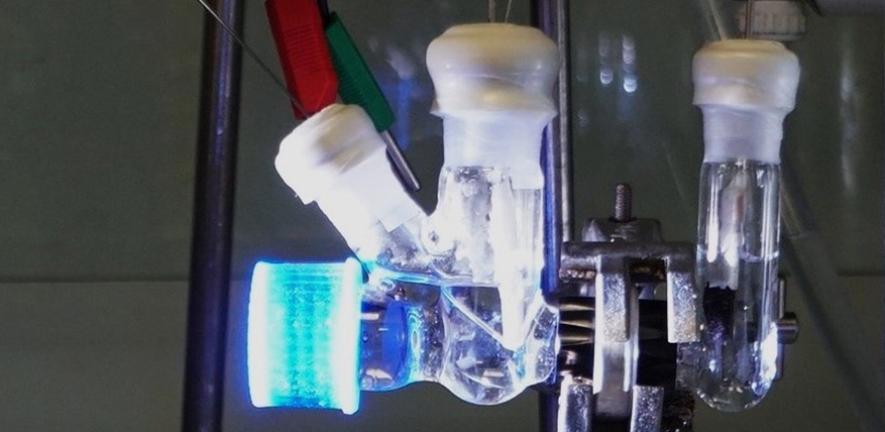

The next step is to test these compounds in vivo (in life) to see if they respond as favorably under less controlled circumstances as when performed in vitro (petri dish) in a controlled laboratory setting. And, there may be even more variations of bioactive fungi to be studied on other species of sloths as well.

We would be wise to preserve the diversity that exists in tropical regions. Representing less than 5% of Earth’s landmass, rainforests contain an estimated 50% of all plant and animal species. It is thought that 50,000 species may be going extinct every year, many before they have even been identified, much less studied for their potential bioactive properties. For those who can’t appreciate tropical rainforests for their intrinsic wonders and aesthetic beauty, it would be smart to save them for greedy purposes of potential personal health. One never knows when that hospital-borne superbug might grab onto you or a loved one. And remember, extinction is forever.