In urban centers throughout the western United States where over 70% of annual runoff originates from large snowy mountains city planners are taking a look at the threat and risk of global warming and climate change on water supplies. The fact that one sixth of the world’s population depends on similar snowmelt resources makes this an issue of global concern.

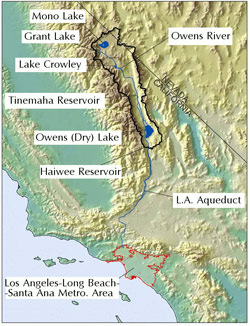

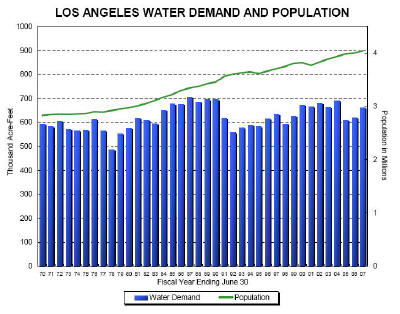

Los Angeles is a case in point. LA sees serious issues affecting its highest quality water supply. A significant portion of the water its 4 million inhabitants use each day starts out in the snowy peaks of the Eastern Sierra Nevada, one of the largest natural reservoirs in the United States. As the snowpack melts it feeds the 340 mile-long Los Angeles aqueduct (L AA) which has seven reservoirs along its length with a combined storage capacity of 300,000 acre-feet. Los Angeles particularly depends on this water during dry seasons.

Los Angeles is a case in point. LA sees serious issues affecting its highest quality water supply. A significant portion of the water its 4 million inhabitants use each day starts out in the snowy peaks of the Eastern Sierra Nevada, one of the largest natural reservoirs in the United States. As the snowpack melts it feeds the 340 mile-long Los Angeles aqueduct (L AA) which has seven reservoirs along its length with a combined storage capacity of 300,000 acre-feet. Los Angeles particularly depends on this water during dry seasons.

At issue is a federal court ruling limiting exports from the Sacramento San Joaquin Delta. In addition projects over the past two decades to protect the environment and improve the flow of water have reduced the aqueduct’s average contribution to the city water supply from two thirds to about one third. Compounding matters has been contamination of the San Fernando Valley River, droughts in the Colorado River and climate change and global warming.

LA’s response is called the “Water Supply Action Plan” and is budgeted to provide $1.5 billion in new infrastructure, water recycling, and conservation programs. The plan is looking for additional groundwater storage sources and supplies along the Los Angeles Aqueduct. The construction of a basin connecting the L AA and the California aqueduct near Antelope Valley is nearly complete and will allow water transfer, better distribution, and conservation.

With increased melting and more runoff the goal is to capture and store more of the melted resource. This requires the upgrade of the current infrastructure and development of new infrastructure and the use of hydrologic modeling to simulate water flow from the mountains to LA. The adaptation strategy also involves studying the changing hydroclimate.

Integral to this is modeling of climate and greenhouse gas emissions, simulations of snowpack accumulation, and snowmelt runoff depending on the time of year. Next is evaluating the current surface water system and projecting how it will act in various scenarios.

Current studies show that with so many variables involved it is difficult at best to make accurate predictions. Scientists are using historical data to try to establish a “baseline” and then to make projections going out 25, 50, 75, and 100 years into the future.